Academik Sergey Vavilov in Paradise Bay, Antarctica, from my kayak

It’s been five years since my awe-inspiring trip to Antarctica. For an adventurer and kayaker like me, Antarctica is the last untamed frontier on earth. It’s a land of icy dreams, ethereal beauty and uncharted mysteries. It’s why people dream of Antarctica and hope for a once-in-a-lifetime journey to the end of the world. But as a polar region affected by climate change, Antarctica is also a trip that will become more risky for future adventurers.

On the opposite side of the globe in Greenland, one of the largest tsunamis ever recorded wreaked havoc on a glacier-surrounded bay back in June. More on this in just a moment. However, it made me think back to something that thankfully didn’t happen while I was in Antarctica. Given the facts that are emerging from Greenland, in hindsight I faced a danger that is now absolutely terrifying to consider.

For Antarctica, it was a warm summer day — greater than 5 degrees Celsius (40 degrees Fahrenheit) — in December when our Russian expedition ship pulled into Cierva Cove, located on the west coast of Graham Land on the Antarctic Peninsula. The Akademik Sergey Vavilov (Академик Сергей Вавилов), a research vessel operated by the Russian Academy of Science, anchored in what appeared to be a peaceful and picturesque cove surrounded on three sides by towering glaciers and filled with icebergs floating like ice in a bowl of water.

There are massive amounts of snow resting above Cierva Cove. It’s a stunning sight to see but also has a dangerous side to its beauty.

A majority of the tourists on our ship prepared for landings in the harbor via motorized rubber Zodiac boats. Meanwhile, my brother, about 15 other kayakers, our two guides and I dressed in our polar dry suits, pulled on our neoprene skirts and crawled into our kayaks.

After sealing ourselves inside our vessels, we slowly paddled away from the relative safety of the Sergey Vavilov. A cool and crisp wind blew against us as we carved our paddles through a soupy patch of glassy ice chunks toward the shoreline.

This was one of the warmest days of our kayaking expedition — in fact, warmer than winter back home in the Great Lakes region of the U.S. and Canada. We paddled a safe distance from enormous icebergs like the one below. We could clearly see complex ridges of compact snow that formed them patiently over time before they calved from the shore. You may know that with icebergs, the tip visible above water level is generally much smaller than what is significantly larger below the surface. Sometimes they flip over and such turning can cause huge waves. But we understood this first danger.

Typical icebergs around the Antarctic peninsula, from our kayaks.

We were also well educated on another peril: calving glaciers at the point where they reach the water. As I stopped to shoot some video on my iPhone, the group paddled ahead of me while I took some shots.

All of a sudden, from a relatively safe distance of about 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) from the face of an enormous glacier, a probably 3.5-meter (10-foot) slab calved into the cove. The roar sounded like a bomb going off in a war zone. Our two expedition guides ordered everyone in the group to turn the bows of our kayaks toward the glacier and huddle all kayaks together in a brace position. Then he yelled at me 20 meters back to paddle full throttle and join up before the five-foot wave arrived. I made it to the group just in time to link up and ride out the waves. But again, this was another danger we prepared for in advance.

Typical glaciers opening at a bay in Neko Harbor, Antarctic Peninsula.

With the calving excitement behind us, we then continued paddling away from the glacier and along the snow-covered shoreline. Gentoo penguins swam curiously under our kayaks and occasionally jumped from the water over the tips of our bows. After four days of kayaking in Antarctica’s frigid waters, witnessing these prodigious swimmers and hearing their social calls never lost its luster.

As we reached what appeared to be the end of the shore at a snowy head, there the icy waters rounded into another cove. We suddenly looked up in awe as huge peaks soared above us, but these weren’t normal peaks. These were cliffs of ice and snow, perhaps 3,000 feet (915 meters) above us! The scale was something I have never seen anywhere before, not in Alaska, Argentina, Canada or Norway.

Some of us were quite warm from paddling for miles in full neoprene and under the white surface of the huge snow mirrors. But we weren’t the only ones roasting. We could hear waterfalls, but we couldn’t see them. They may have been hidden by the blue crevices they fell through, but we could hear the unmistakeable sound of water falling into the bay. Some of this snow was likely thousands of years old and it was packed into tremendous volumes. We looked up to the tops in silence and just stared in utter disbelief. We were probably no more than 300 meters (1,000 feet) from the sides of the cove.

To give you perspective how tall this is in Cierva Cove, the kayak in front of me is more than one kilometer from the glacier. It is much taller than it appears in the photo.

A few moments later we heard and witnessed a few small pieces calve of into the bay. The boom sounded like a canon as the ice hit the bay and small waves rushed toward us. It was nothing threatening but it reminded us to keep a safe distance. Then our guides asked us to proceed to the middle of the cove at least 600 meters (2,000 feet) away from the edges of the bay.

One of my instructors had kayaked a combined 500 kilometers (300 miles) during the last few seasons in Antarctica — probably more than anyone in history. Ian was also a glaciology post-graduate student at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada. He knew every type of snow and ice and seemed to be as transfixed as I was by the depth of how far back the snow went. Then I started to notice something a bit disturbing. Some huge slabs at the top of the snowy cliffs — probably the size of battleships — looked to be fractured and leaning. I turned to Ian and remarked on my observation.

“Is it just me, or do some of those snowy clifftops not look stable?” I asked.

“No, I was thinking the same,” Ian said.

And then I asked a frightening question. “What would happen if just one small slab … maybe 20 meters long fell from that height?”

“We should probably keep moving,” he said with a slight grin and a little understated Canadian humor.

It was at that moment I began to realize that the beauty surrounding us here at the end of the world was special but also a potentially deadly beauty. But it wasn’t until this past week that I began to realize how lethal.

So back to that story from Greenland with one of the largest tsunamis ever recorded on June 17. When we think of powerful tsunamis, we tend to think of the Tohoku tsunami that hit Japan back in 2011. That tsunami, cause by the massive displacement of movement along a massive Pacific earthquake fault, generated a wave about 10-meters high (33 feet) that killed more than 18,000 people.

The Greenland tsunami was a different phenomena altogether, known as a “mega-tsunami.” And you will never believe this. That wave reached more than 100 meters high (328 feet) after a glacier-held rock fell nearly a kilometer down into the sea! The mega-tsunami then rushed 20 kilometers (12 miles) down the bay at more than 180 km/hour (110+ miles/hour) and completely destroyed the small Greenlandic community of Nuugaatsiaq located on an island within the fjord. To put this in perspective, the landslide was so powerful it registered as a 4.1M earthquake on seismographs.

Mega-tsunamis are caused when a huge object such as a piece of a volcano, mountain or huge glacier impacts a shallow body of water. The tsunamis are mostly localized to a smaller area but they create a huge movement of water proportional to their area that can dwarf earthquake-caused tsunamis.

When I was in western Norway a few years ago near the famous tourist destination of Geiranger, I toured the Storfjorden — one of the most beautiful places in Scandinavia. It was then I first learned the hidden dangers that fjords, like those in Antarctica, Norway and Alaska, hide in plain sight.

The popular Norwegian tourist town of Geiranger is living on borrowed time.

Above the Storfjorden, the 900-meter-high Åknesfjället looks like a very ordinary mountain. However, each year a 700-meter-long and 30-meter-wide crack grows each year. Someday, it’s a geological certainty that the entire 900-meter (3,000-foot) slab of the mountain will dive into the fjord. When it does, the narrow fjord will amplify a wave more than 80-meters (250-feet) high that will destroy the picturesque village of Hellesylt, the industrial port of Stranda and the world-famous town of Geiranger.

However, these two mega-tsunamis pale in comparison to the largest mega-tsunami ever recorded. Back in 1958, the Lituya Bay tsunami in Alaska reached 530 meters (1,740 feet high)! Believe it or not, a father and son lived to tell about it. Imagine a wall of water almost the same height as the Freedom Tower of the World Trade Center in New York City!

Could a mega-tsunami happen in Cierva Cove, Antarctica? Ominously, it shares the same type of geography and glacial features as Lituya Bay. And if we were to be there when it does happen one day, most likely our bodies would never be found! I am certainly glad that we won’t be there to find out because it is an absolutely petrifying thought to consider a monster wave more than 530 meters tall coming straight toward you at the speed of a small airplane! However, the changing climate is making these hazards much more dangerous as the meltwater during warmer summers increasingly fractures these glacial cliffs.

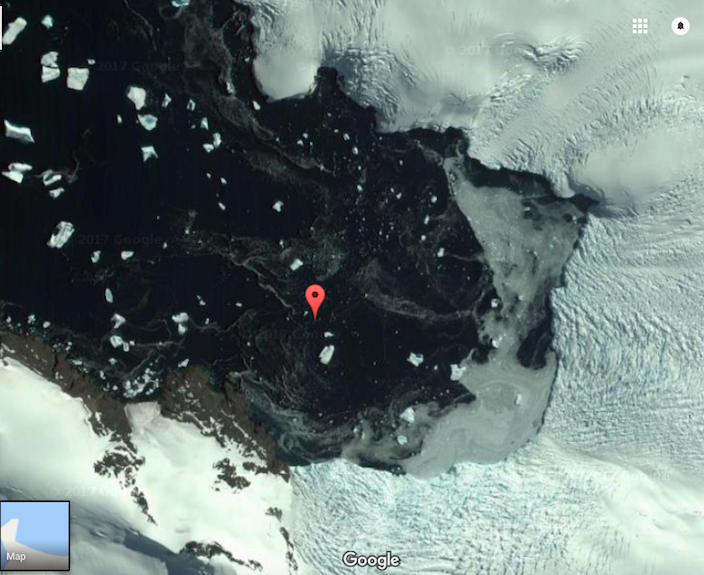

View of Cierva Cove from Google Earth

To be factually correct, climate change is much more accelerated in the northern hemisphere’s polar regions than in Antarctica. Nevertheless, climate change is a factor that many scientists believe recently dislodged the Larsen C ice shelf, roughly the size of Wales, from the eastern side of the Antarctic Peninsula.

If you want to see video of this kayaking adventure to the end of the world, watch video from my journey below. And despite the kayaking risk, I would do it all over again!

Categories: Antarctica, Uncategorized

It is incredible naive of some leader in the world to ignore climate change. There can be said to be perilous times ahead for humanity!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree, Mel and Susan.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Truly breath taking photography. Hard to visualize waves of that magnitude. Would you go again?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Without hesitation, Bob!

LikeLike

Hi, Kevin! Awesome post and gosh, it was fun watching your video and reliving that trip. I would do it all over again, too. No doubt about that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Shari, Jeff and I feel the same way. It’s going to be hard to top that trip. But I am up for the challenge!

LikeLike